Installed inside ‘In Ictu Oculi – In the Blink of an Eye’ © James Morris

Installed inside ‘In Ictu Oculi – In the Blink of an Eye’ © James Morris

Between 2018 and 2021, a number of ceilings, tiles, floors, plasterwork (yeserias) were recorded in high resolution and recreated in by Factum’s technicians and artisans in Madrid.

The outcome is a portal into Spanish Renaissance and early Baroque thinking and a collection of mutually beneficial collaborations that redefine sharing, connoisseurship and preservation.

Wallpaper

The wallpaper design was conceived as a composite with many influences and ingredients. It is based both on patterns produced by the wall coverings made by the Real Fábrica de Papeles, Madrid, in the 18th century, and the frescos designed to mimic painted cloth on the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel. The artwork was developed using photographs of actual cloth and architectural details that have been digitally reworked. The pilasters are based on those of the Sepulcro de Doña Catalina de Ribera (1521) by the Genovese sculptor Pace Gazini, made for the Monastery of Santa María de las Cuevas (also known as Monasterio de la Cartuja), Seville, where it can be seen today.

Each element of the composition is ‘overpainted’ using brushmarks borrowed from Diego Velázquez. In particular, the following paintings now held in British collections; An Old Woman Cooking Eggs (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh), and The Waterseller of Seville and Two Men Eating at Humble Table (Apsley House, London). Velázquez’ brushmarks mimicking stone carving and material decay also form the frieze, cornice and architectural moulding. The delicate border of golden thread is taken from embroidery found in the Palio de Nuestra Señora del Valle, Seville while the heraldic shields are from different ‘cofradías’ (religious organisations associated with different churches) that are paraded during Semana Santa.

Production process from left: photograph, application of texture, addition of brushmarks and merging of all layers © Factum Foundation

© James Morris

Tiles

The extraordinary glazed ceramic tiles that decorate the walls in the Casa de Pilatos in Seville have a defining presence in the Palace and represent a peak in the formal expression of the ‘cuenca’ method of tile making. This technique was developed in Seville and used in both religious and civil buildings throughout the 1500’s. The tiles were produced in Diego and Juan Pulido’s workshop in Triana, Seville, in 1538.

The two techniques used to make ornamental wall tiles in Seville were the ‘cuerda seca’ and ‘cuenca’ methods. The ‘cuerda seca’ is earlier and ideal for making rectilinear geometric patterns like Mudéjar lacework. This method uses string to subdivide the tile onto which the different coloured glazes were poured. During the firing the string burns away, leaving a relatively uniform surface of different colours. At Casa de Pilatos, cuerda seca tiles are found in one of the earliest rooms in the Palace, the Capilla de la Flagelación.

The cuenca technique (also called ‘de arista’ or ‘de labores’) appeared with a desire to make decorations less geometrically rigid, and more similar to textiles, fabrics and embroidery. The mould contained a negative sunken impression so that the clay tile ends up with positive raised lines for separating the coloured glazes. The first cuenca moulds were carved in wood and later made in metal which produced cleaner and sharper detail in the finished tiles. The mechanisation of the process is part of its aesthetic appeal. In their contract, Diego and Juan Pulido committed to delivering 2,000 tiles a week, illustrating the scale of production possible at that time.

The third type of tile here has no prescribed relief that defines a clear pattern. Fluid glazes allow colours to glide over irregular clay surfaces creating beguilingly spontaneous abstractions. Games of shifting figure-ground and subtle variations in the way colours are combined all contribute to animating the surface through creating dynamic spatial relationships. This, together with the brilliance of the coloured glazes, the mysterious axonometric projected language of the border tiles and the natural resistance of ceramics to aging, creates an overall effect that is curiously modern.

The tiles in Casa de Pilatos were recorded in 2018 using the Lucida 3D Scanner and composite photography as part of the fieldwork training with Columbia University’s GSAPP and more tiles were recorded by a Factum Foundation team in 2020. To produce the facsimile, the surface was 3D printed with a Canon elevated printing system to recreate the relief, which was then moulded, cast in acrylic resin, gesso-coated and printed on Factum’s flatbet inkjet printer. The final layer of transparent varnish was applied by hand.

Eduardo Lopez recording the colour information of the ceramic tiles with panoramic composite photography © Factum Foundation

Floors

The facsimile floor is based on the traditional terracotta tiles commonly found in Seville and other parts of Spain. It was made by Factum Arte after recording the tiles in 3D with photogrammetry at Casa de Pilatos. With permission of Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, the data was used to CNC mill, mould and cast the 3D surface in simulated terracotta to create an authentic floor covering.

Ceilings

The ceilings created by Factum Foundation for the Spanish Gallery are accurate reproductions of specific existing ceilings or new interpretations inspired by standard motifs and patterns. The intent was to provide both a level of unity to the Spanish Gallery as a whole, but also to recall each of the facsimiles’ context of origin.

After recording the original elements using photogrammetry and composite photography, each ceiling has been adapted to the original timber structure of the rooms in the Spanish Gallery. All details were hand painted on plywood.

Damian Rojo working on the details of the Mudejar-style ceiling © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

This new design by Factum Arte is inspired by traditional Spanish Mudéjar timber ceilings of the 15th-17th centuries. The original ceiling is a modular design formed by five repeating sections. The ceilings are the result of an approach to pattern-making that uses geometric principles to generate patterns of great complexity and beauty, characteristic of Islamic and post-Islamic decoration in Spain.

The ceiling is composed of a language of geometric patterns that start from a basic module and unfold into an infinity of shapes. The basic element is the band-like lace that creates the linear pattern from which the decoration is formed. The repeating geometry forms star-like encounters. According to Spanish architect and restorer Enrique Nuere, the complex patterns are made using only three right angled set squares.

Detail of the Mudejar-style ceiling created by Factum © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

The Mudejar-style ceiling under production © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

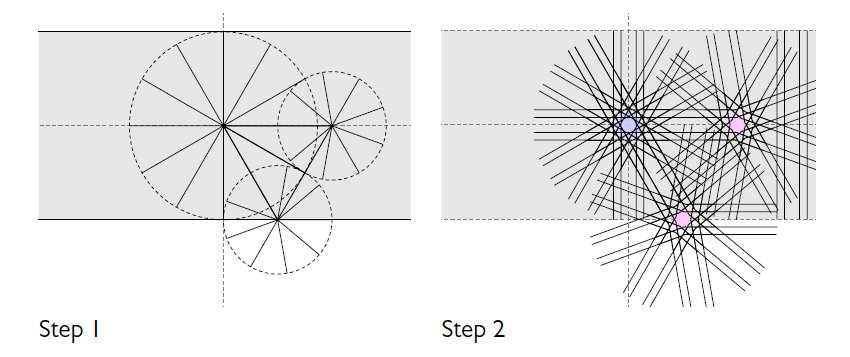

The following images, prepared by Carlos Bayod, reveal the underlying structure of the ceiling derived by Factum from the principles of Mudéjar design and made using digital technologies.

Step 1: The total size of the original ceiling is approximately 750 x 300 cm, divided into five similar sections.

The first step consists of placing a 12-pointed star at the centre of a section. Then, at the intersection of one of the 12 radii, with the edge of the section, a 9-pointed star is placed. The position of the other stars is determined by the resulting intersections of specific extended radius with the edges of the sections.

Step 2: To adapt to the dimensions of the room at the Spanish Gallery, only the three central sections are reproduced. Once the main stars are placed, each radius is converted onto a double-lace, which will be the basic decorative motif.

Step 3: A careful observation of the ornamental design results in a system of intersections among the laces that will define the basic module for the ceiling.

Step 4: The resulting basic module after refining the design, with the laces intersecting above or below each other, in alternation. This is the minimum unit of ornament that will compose the full area of the ceiling.

Step 5: Full development of the ceiling through the repetition and rotation of the basic triangular module.

Step 6: Based on the photogrammetric data of the original ceiling, the inner lines that mark the divisions within the laces are drawn, making sure that the intersections work fine for all specific cases throughout the ceiling. The resulting stars and polygons between the laces are filled with hatches so they become areas for future extrusion and modelling. Each line has a specific width assigned, in anticipation to the CNC-milling.

Step 7: The final system of lacework, stars and polygons in between is complete, ready for 3D modelling and fabrication. The final adaptation to the specific proportions of the room is carried out as needed. The resulting pattern resembles a geometric abstraction of the stars in the sky.